Register to get 2 free articles

Reveal the article below by registering for our email newsletter.

Want unlimited access? View Plans

Already have an account? Sign in

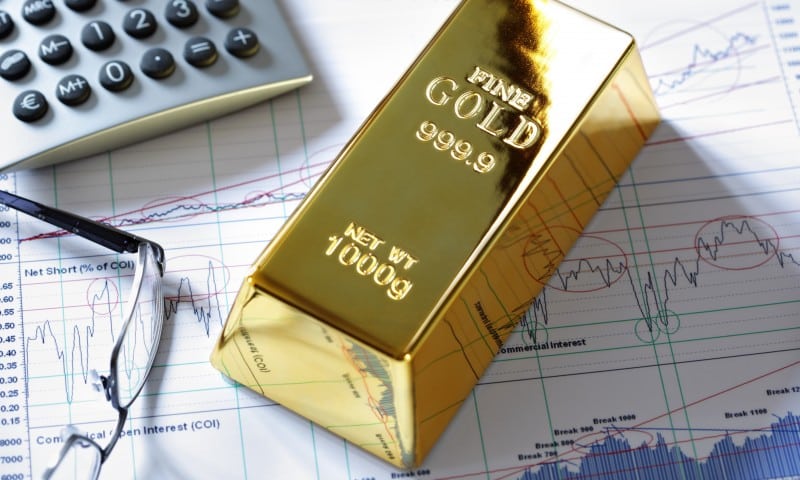

The gold price has stabilised, and the slump in gold hallmarking has bottomed out. And now that the commodity traders are losing interest, MICHAEL NORTHCOTT asks whether the scrap-buying craze has caused any lasting change to the market.

Two very significant trends have appeared that will likely have a profound effect on the industry over the coming months and years. First, gold volumes passing through assay offices have finally stopped shrinking – 2013 was the first full year in 10 years in which the volume of pieces hallmarked did not dip yet further. True, the drop since 2003 has been catastrophic, and we’re probably unlikely to see a sudden surge restoring the figures to their heights. But progress can only be measured by improvement, and improving they are.

Second, the gold price itself is falling. For the uninitiated, it’s worth pointing out that jewellery industry really has very little effect on the gold price; it’s investors and financial institutions that matter. Recession and economic uncertainty regularly result in gold being identified as a safe haven, because property prices and company values everywhere are falling. It produces a kind of ‘back to basics’ approach meaning the gold standard (which Churchill did away with) is unofficially re-adopted.

According to the World Gold Council, there were outflows of 881 tonnes from ETFs (exchange traded funds) in 2013, and even though consumer demand for this precious metal rose 21 per cent globally, the net result was that global gold demand in 2013 was 15% lower than in 2012, hence the lower gold price.

A reflection of how investment is the dominant influence on price rather than jewellery demand, is apparent when you consider the developing world. Jewellery demand increased by 29% from 519t to 669t in China, and by 11% from 552t to 613t in India, reaching 2,209t globally, the highest figure seen since the onset of the financial crisis in 2008. And yet total demand experienced a significant drop.

CALMING DOWN

Thanks to all of this, the contrast between the height of the rush and now is stark: the 10-year high point for scrap gold was 6th September 2011, where it reached £1,182.82 per oz, and the spot price at the end of January 2014 (shortly before the Birmingham Assay Office’s Michael Allchin gave an upbeat report on the topic at Spring Fair), was £749.67. At the beginning of 2013, the the price very nearly reach the peak again, comfortably breaching the £1,100/oz mark, but it has since come down significantly.

Gary Williams, director at Presman Mastermelt and chairman of the British Jewellers’ Association (BJA), says that many of those who entered the scrap-buying game for a quick fortune “have had to get out of it altogether – they just can’t get a big enough margin to sustain the business any longer”. He adds: “All of the established bullion houses that have been building their business over many years and through calmer times in terms of the market, will have no difficulty re-stabilising, because they had sustainable core business models before the gold rush began to happen.”

All of the established bullion houses that have been building their business over many years and through calmer times in terms of the market, will have no difficulty re-stabilising, because they had sustainable core business models before the gold rush began to happen.

Miles Mann, whose group of companies includes a bullion operation as well as jewellery retail outlets, is broadly in agreement, although he thinks there will be some lasting change because of increased competition. He says: “Even though most of the popups have now ‘popped back down again’, not everyone who jumped on the bandwagon did so for this one particular revenue stream. Organisations such as the Bureau de Change or newsagents, added scrap-buying as a way of augmenting a business which was already sustainable,” and this, he explains, means there is a higher level of competition in places where the jeweller and the pawnbroker used to be the only buyers of scrap.

So what are we to expect, now that gold is heading back for a price point that consumers can actually afford (and just as the economic upturn puts some money back in their pockets)? Can we expect the price to stay lower, consumers to start buying gold again and the hallmarking figures to rise again? Not necessarily. Given that, as previously mentioned, the volatility of the gold price is dictated by global economic forces and not domestic jewellery demand, there is plenty of potential for investors to get jittery again. Alex Baird of Baird & Co is not convinced that we’ve seen the end of the gold rush. “It is true that it has been quite quiet for a while because of the ETF dumping, but it is showing a bit of a recovery. We may have turned a corner economically, but there is still a lot of angst around the world in financial markets – Europe is not doing particularly well – so it is not guaranteed that investment will not push the gold price up again.”

TECHNOLOGY DILUTE

All things considered, there is not much point in the industry collectively holding its breath for the days when 23 million gold pieces were being hallmarked every year. Consumer spending at the £300 – £1,000 mark has been seriously diluted by the rise of smartphones and tablets. The under-30s age group hasn’t suddenly acquired a load ofextra money to buy an iPhone; instead, this is money that in days gone by would have been spent on a ring, a necklace or even a watch. Furthermore, high hallmarking figures back in 2004 were precipitated by a credit-fuelled boom at its very peak. Even when the economy is legitimately back in growth mode, it is doubtful that we will see that kind of consumer spending again even with a more sensible gold price.

But this isn’t to say that these figures do not represent encouraging reading. If the gold price levels out at this lower mark on the chart, then the jeweller stands a good chance of finding some margin in precious metal pieces again. This, combined with the economic upturn means it should be merely a matter of time before the general public is once again keener on gold. It’s been a good run for the bullion houses, but now that the scrap market appears to be settling down, independent jewellers will not have to turn to it as a way of trying to coax in some additional revenue. They can get back to selling pieces rather than buying them.

Number of items hallmarked (millions):

| Year | No of pieces (millions) |

| 2004 | 23.6 |

| 2005 | 19.4 |

| 2006 | 16.7 |

| 2007 | 15.8 |

| 2008 | 10.4 |

| 2009 | 7.0 |

| 2010 | 5.8 |

| 2011 | 4.4 |

| 2012 | 4.1 |

| 2013 | 4.1 |