Register to get 2 free articles

Reveal the article below by registering for our email newsletter.

Want unlimited access? View Plans

Already have an account? Sign in

As any company reliant on a handful of large customers knows well, exposure can kill. Having a large contract pulled after investing in people or kit is a painful – and sometimes catastrophic – bump in the road. But it is not always possible to avoid this scenario – you can inadvertently be at the mercy of a force beyond your control.

I draw the analogy, because to my mind the jewellery industry is and always has been at the mercy of the international investment market – a large and faceless force which can turn on a sixpence. When times get tough, insitutional investors and the finance industry get busy ditching other more volatile assets and buying up gold in the commodity markets. They’re looking for stability, a safe bet. This sudden increase in demand pushes the price up, and suddenly anyone who works with gold finds their cost base has increased overnight.

This, as we are well aware in this industry, was exactly what happened in the stormy 2008-2013 period, where the gold reached record highs and the general public, instead of buying jewellery, cashed in all their scrap. This had the temporary effect of keeping many jewellers afloat – they were able to make a few quid buying the scrap and selling it on to bullion houses for a profit.

But once the scrap buying craze meant the nation’s households had been emptied of their old jewellery, the gold price remained very high, and in order to make any margin at all, many jewellers had to sell comparable pieces at much higher prices than just a few years previously.

The industry is still plagued by metal prices that move in ways they did not used to: if you study a 30-year graph of them, the post-2008 peaks are unparalleled at any time in recent history.

Most recently, according to the World Gold Council, gold has “staged a spectacular rally” in the first quarter of 2016, with the price in US dollars rising by 17% – the “best performance in three decades”. You can gather the WGC is not writing with the mood of the independent jeweller in mind.

In this particular report, the WGC adds: “We believe that market uncertainy and expansionary monetary policies will continue to support both investment and central bank demand. This, combined with an analysis of bull-bear cycles, suggests we may be entering new bull market for gold.”

Much commentary is written in the jewellery trade press – both in the UK and in overseas magazines – about the fact of this volatility and what it means for manufacturers and high street jewellers. But in the light of an ominously opaque piece of financial writing like that, we thought our readers might want to learn about why these market behaviours happen.

The World Gold Council periodically produces reports on prices, market behaviour, and what the major influences are at any given moment. In their latest such offering, which they have kindly allowed us to reproduce in Jewellery Focus, there are some very interesting takes and analyses on the state of the market.

We have entered a new and unprecedented phase in monetary policy. Central banks in Europe and Japan have now implemented Negative Interest Rate Policies (NIRP).

The long term effects of these policies are unknown, but we see discouraging side effects: unstable asset price inflation, swelling balance sheets and currency wars to name a few. Amid higher market uncertainty, the price of gold is up by 16% year-to-date – inpart due to NIRP.1

History shows that, in periods of low rates gold returns are typically more than double their long-term average. Looking forward, government bonds are likely to have limited upside, due to their low-to-negative yields and, in our view, would be less effective than gold in mitigating risk, ensuring portfolio diversification, and helping investors achieve their long-term investment objectives.

Portfolio analysis suggests that gold allocations in a low rate environment should be more than twice their long term average. We believe that, over the long run, NIRP may result in structurally higher demand for gold from central banks and investors alike.

Exploring the unknown: unconventional monetary policies are changing the investment landscape

In the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis, central banks resorted to unconventional tools like Zero Interest Rate Policies (ZIRP) and Quantitative Easing (QE) – which had been first pioneered by Japan in the early 2000s – to (try to) stabilise prices and/or maximise employment as traditional measures had been exhausted.2

More recently, between mid-2014 and early 2016, central banks in Denmark, the euro area, Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland have all implemented NIRP – thus breaking the ‘zero lower bound’.3 This means that commercial banks have to pay to deposit balances with central banks.

NIRP was largely devised to counteract deflationary pressures and, in some cases, currency appreciation. However, negative nominal interest rates have short and long-term consequences. Their effect will likely be felt by investors (big and small) and by other central banks.

Investors (including central bank reserve managers) now need to assess the risk-reward of investing in assets with negative return expectations. But the implications may be more far reaching. Such policies may fundamentally alter what it means to manage portfolio risk and could extend the time needed to meet investment objectives.

As a result, we expect that demand for gold as a portfolio asset will structurally increase. We believe there are four reasons for this, as NIRP:

- Reduces the opportunity cost of holding gold

- Limits the pool of assets some investors/managers would invest in

- Erodes confidence in fiat currencies due to the threat of currency wars and monetary interventions

- Further increases uncertainty and market volatility as central banks run out of effective policy options to combat inflation/deflation and/or spur growth

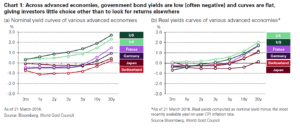

It costs little, if anything, to hold gold under NIRP

The link between gold and interest rates happens through investment demand.4 Low interest rates reduce the opportunity cost of holding gold. Negative rates magnify this. Negative sovereign debt yields in Switzerland and Japan extend out to 10 years, while those in France and Germany are negative out to 5 years (Chart 1a). Even interest rates in the US and UK are extremely low across the curve, with up to 2-year debt yielding less than 1%. In real terms, the picture is even bleaker. Only yields in the UK are positive for maturities higher than 3 years and just a few long-term bonds yield more than 1% (Chart 1b).

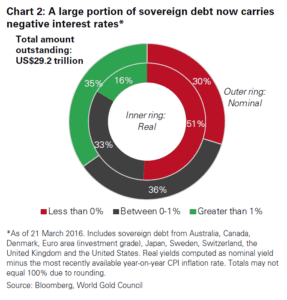

With fewer options to invest in, gold shines

NIRP significantly reduces the likely pool of assets that investors may hold. In the current negative nominal interest-rate environment, about 30% of high quality sovereign debt (more than US $8 trillion!) is trading with a negative yield, and almost an additional 40% with yields below 1% (Chart 2). When yields are adjusted for inflation, the figures are even starker: 51% of sovereign debt (US$15 trillion) is trading with negative real yields and only 16% yields more than 1% in real terms.

Unless investors are willing to accept a loss-making investment strategy, they may need to consider increasing their holdings of gold. We believe this should resonate especially well with pension funds and foreign reserve managers whose investment guidelines are typically stricter and who hold a large portion of bonds in their portfolios. It is also relevant for investors with limited tolerance for risk, as well as those who have increased their stocks holdings due to the low rate environment.

The unnerving spiral of currency wars and intervention

Negative interest rate policies were designed and implemented to fight against deflation and currency appreciation pressures, especially vis-à-vis the US dollar. Nonetheless, currencies from all advanced countries/regions that implemented negative rates have actually appreciated against the US dollar, year-to-date, ranging from about two to seven percent.

The longer this situation persists, the greater the likelihood some central banks may pursue intervention measures. Conversely, while gold is a de-facto currency in the monetary system, it is the only one that is not targeted directly by, and doesn’t respond negatively to, expansionary monetary policies.

The uncertain outcomes of untested tools

Investors are growing increasingly concerned about the effectiveness of NIRP. Investors are still digesting the unexpected decision by the Bank of Japan to enter the negative interest rate fray in late-January 2016, and there is a “growing perception in financial markets that central banks might be running out of effective policy options”, according to the BIS Quarterly Review released on 6 March 2016.5

Claudio Borio, Head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the BIS, noted the following day that confidence in central banks was “faltering”.6 The recent increased turbulence in financial markets serves to highlight the need for portfolio diversification and effective risk management – tasks at which gold has traditionally excelled.

Given the low interest rate environment, we believe it is almost certain that investors will not obtain the same level of returns from bonds as they did over the past two decades. Our analysis shows that, even when using broader bond indices, current yields are a very good predictor of actual returns in the future. 7 Put simply, this means that bond holders can expect little return, or even negative return, from their sovereign bonds.

In our view, investors should not rely solely on bonds to meet liabilities and reach long-term savings goals.

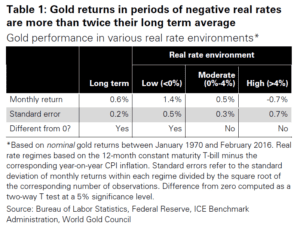

Intuitively, gold returns should be higher in periods of negative rates given the low opportunity cost of holding it and its status as a high quality, liquid asset. And while negative nominal rates are unprecedented, negative real rates have occurred often in history. Using these as a proxy, our analysis shows that (Table 1):

- When real rates are negative, gold returns tend to be twice as high as the long term average

- Even if real rates are positive and as long as they are not significantly high (4% in our study), average gold returns remain positive

- Falling rates are generally linked to higher gold prices; yet rising rates aren’t always linked to lower prices

Bonds may not be as effective as gold in balancing equity risk under NIRP (or ZIRP)

Under NIRP, investors may need to rebalance their portfolios in the short-to-medium term. But in the long term, the implication may be even more compelling. Bonds generally help balance the risks inherent in portfolios. Low yields, however, not only promote risk taking, but also limit the ability of bonds to cushion pullbacks in stocks and other risk assets in investment portfolios.

Investors may also require longer periods to achieve their objectives (manage foreign reserves, fund their retirement, fulfil liabilities, etc.) Our research shows that gold can help investors balance portfolio risks in this largely unprecedented environment.8

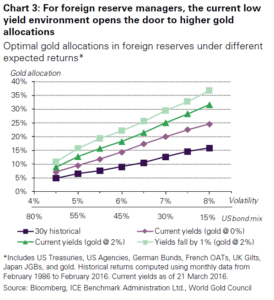

For central bank reserve managers who usually invest in a more limited set of assets, we have found that the optimal gold holding in the current low yield environment would significantly increase (Chart 3).9 In particular, we find that even under conservative assumptions for gold returns:

- Optimal gold holdings in foreign reserve portfolios increase 1.5 times

- The multiple increases to more than 2 times if yields fall 1% from current levels (or if current yields persist but gold returns are close to their historical average)

For example, the optimal gold allocation in a foreign reserve portfolio with 55% of its holdings in US bonds (akin to the average holdings by central banks) would increase from 7.6%to 15.7% assuming gold returns only 2% per year, and it could go as high as 19.3% if yields were to drop 1% from current levels (or if yields were unchanged but expected gold returns were 4% per year).

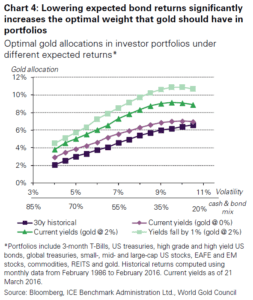

For investors with portfolios that have a mix of stocks and bonds (Chart 4) we found that strategic gold allocations under the current low yield environment are:

- 1 to 1.5 times higher they would be if average bond yields were closer to their 25-year average, depending on the portfolio mix

- 1.5 to 2.2 times higher than they would be if bond yields were to fall 1% from current levels (or if current yields persist but gold returns are close to their historical average)

For example, in the current global low yield environment and even under conservative assumptions for gold returns, our research shows that an investor with a 60/40 portfolio may hold up to 8.7% in gold (up from 5.5% under historical assumptions for bond return expectations), and up to 10% if yields were to fall 1% further (or if current yields were unchanged but expected gold returns were 4% per year).

While these examples use US-dollar portfolios, similar results apply to euro and pound-sterling investors.

An environment that promotes gold demand

Central banks have been accelerating the use of gold to diversify their reserves since the 2008-2009 financial crisis. In the second half of 2015 alone, central banks bought more than 336 tonnes of gold – the largest semi-annual total on record.10 The acceleration of such purchases, across a diverse range of countries, highlights the fact that diversification of foreign reserves remains a top priority for central banks.

As foreign reserve managers all over the world continue to grapple with the challenges of negative nominal interest rates, we expect to see record amounts of central bank gold purchases in 2016 (and beyond). Similarly, heightened uncertainty is driving investor flows.

Year-to-date, gold-backed ETFs have increased their holdings by more than 330 tonnes worldwide11 – some of this increase, as we see it, is linked either directly or indirectly to negative rate policies, among other factors.12 Partial data and anecdotal evidence suggest that bar and coin demand in developed markets is also surging – in particular, demand for American Gold Eagles more than doubled in January and February, relative to the same period in 2015.

While some of these flows may be temporary, we believe that the prolonged presence of low (and now even negative) rates has fundamentally altered the way investors should think about risk and may result in a broader use of assets like gold to manage their portfolios more effectively and preserve their wealth over the long run.

Reproduced by kind permission of the World Gold Council. This feature first appeared in the May 2016 feature of Jewellery Focus.